In the post “Time synchronisation in local nets” I described the uses of DCF77 receivers to get the standard time from PTB’s atomic clocks. The choice of AM receiver modules was commented on as well as their connection to a µController like a Raspberry Pi.

Here we discuss the decoding of the DCF77 AM signal by C software on a Raspberry Pi.

The nature of the AM signal

At the begin of all seconds of a minute but the last one the amplitude is reduced to 15% for either 100 or 200 ms. For the rest of the one second or two second period the full (100%) amplitude is transmitted.

The AM receivers’ modules digital output is usually

• HI (1, true)

for the 15% modulation time and

• LO (0, false) for the rest of the 1 or 2 s

period.

But it can be the other way round – what the software should handle by,

e.g. an option - - invert.

For the modulation time

• 200ms means true and

• 100ms means false.

Hence, the information we must acquire and decode is

a) an 58 bit telegram in every minute and

b) the start time of the modulation period.

a): The telegram starts with 14 bits of secret commercial information. The remaining 44 relevant bits contain all time and date information. The code is simple and well published.

b): The time should be captured as exactly as possible, best as µs time stamp with 20..50µs accuracy. With the time stamp of the modulation flank and their DCF77 time we get the correction respectively setting of our system time – for the use of DCF77 as our system’s redundant or only time source.

So in the end, it’s all about getting the time (time stamps) of the modulation flanks.

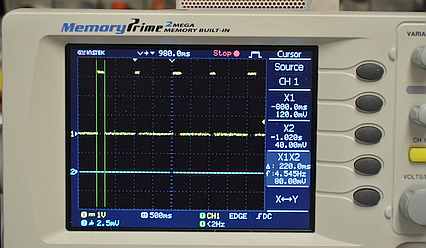

Sampling the AM signal

We can think of three approaches

A) read the receiver signal in the 1 ms cycle,

B) have an interrupt handler for both signal flanks or

C) exploit the abilities of pigpiod.

Having a runtime or framework providing PLC like cycles, as described in Raspberry for remote services (see publications) and used in most of our controller projects, approach A is feasible. On the other hand, when wanting DCF77 as substitute or redundancy for NTP the sync would have to be at least one order of magnitude better than the fastest cycle’s timing: a reason to exclude A).

Generating sequence of time stamped events to be handled later in in an other thread or process is per se a good approach. And an interrupt handler (B) could do this. Raspberry processors have an interrupt system allowing flank interrupts for any GPIO. But the handling is complicated and the application requires sudo privileges.

A comprehensible C solution with GPIO interrupts is hardly found. Some

libraries or frameworks employ a fast sampling thread +

interthread/interprocess communication – and call it “interrupt”.

Well the approach is OK. It’s what what A) does too slow (what could be

mended by an extra asynchronous fast cycle) and what C) (see below) supports

perfectly. But selling it as interrupt is label fraud.

Well I’m an aficionado of Joan N.N.’s pigpiod library. See the chapter in question and the literature list in above mentioned publication. So, not surprisingly, I exploit special abilities of a library used anyway.

Capturing modulation flanks with pigpiod

As said, pigpiod is our preferred approach to Raspberry IO and the only one we use for real control applications. It defines a server or daemon which does all initialisations and has control over all functions of the GPIOs used. This server has to be started with sudo to run forever in background. On all Raspberry Pis where we installed it we start it at boot by a (sudo) crontab entry:

@reboot /usr/local/bin/pigpiod -s 10

The -s 10 means pigpiod running ia 10µs cycle instead of a

default 5µs one. For all our applications sofar a 20µs delay, time stamp and

signal generation accuracy was sufficient. (The fastest would be 1µs.)

Programs doing (process) IO just communicate with the daemon by

• socket (as in the

GPIO with Java project),

• pipe (never used here) or by

• a set of C functions.

pigpiod allows to set a callback function for the flank(s) of an input pin:

set_mode(thePi, dcfGpio, PI_INPUT); // make dcfGpio input

if (dcfPUD <=PI_PUD_UP) // Raspberry Pi's pull up is sufficient for open

set_pull_up_down(thePi, dcfGpio, dcfPUD); // collector output stages

dcf77callbackID = callback(thePi, // register dcf77receiveRec

dcfGpio, EITHER_EDGE, &dcf77receiveRec); // as callback function

Semantically this is not so far from interrupts. But we avoid all interrupt complications (and dangers) and get 32 bit system time stamp for every signal flank in 1µs resolution and about 15µs accuracy as extra.

/* The actual respectively last modulation period data received. */

dcf77recPerData_t dfc77actRecPer;

/* DCF77 receive recorder.

*

* This is a pigpiod callback function for .... (in other file)

*/

void dcf77receiveRec(int pi, unsigned gpio, unsigned level, uint32_t tick){

uint32_t const dif = tick - dfc77actRecPer.tic;

dcf77lastLevel = dcfInvert ? !level : level; // handle AM receiver polarity

if (dcf77lastLevel) { // in 15% modulation, i.e end of last period

dfc77actRecPer.per = dif; // calculate duration

dfc77ringBrecPer[dfc77ringBrecWInd] = dfc77actRecPer; // put in FiFo

++dfc77ringBrecWInd; // signal FiFo write respectively period end

dfc77actRecPer.tic = tick; // start of new period

} else { // full (100%) signal

memcpy(dfc77actRecPer.sysClk, lastSysClk, 12); // log time for current

memcpy(lastSysClk, stmp23 + 11, 12); // log time text for next period

dfc77actRecPer.cbTic = get_current_tick(pi); // call back tick

dfc77actRecPer.tim = dif;

dfc77actRecPer.sysClk[12] = dfc77actRecPer.sysClk[13] = '\0';

}

} // dcf77receiveRec(int, 2*unsigned, uint32_t)

For every modulation period the callback function shown fills a record of

dfc77actRecPer of type dcf77recPerData_t and fills it in a

FiFo (ring buffer).

The structure is (excerpt with comments shortened):

/** Data for one received DCF77 AM period. */

typedef struct {

/** The piogpiod time tick in µs. */

uint32_t tic;

/** The system time as text hh:mm:ss.mmm at period start for logging convenience.

*

* It is the time when the call back function for start of 15% AM is called.

*/

char sysClk[14]; // text provided by rasProject_01 framework

/** The system tick at second's start in µs.

*

* It is the time of entering the call back function for 15% AM.

* By the pigpiod event to callback entry delay cbTic should be later than tic. By

* their difference an apparent system-DCF77 time difference has to be shortened.

*/

uint32_t cbTic;

/** The 15% modulation's duration in µs. */

uint32_t tim; // 100ms: FALSE, 200ms: TRUE

/** The period's duration in µs. */

uint32_t per; // 1s: second's end, 2s: minute's end

} dcf77recPerData_t;

With

• start time .tic, ideally every real atomic second,

• period .per, ideally either 1s or 2s, and

• modulation time .tim, ideally either 100ms or 200ms,

recorded over a minute we got all needed to decode and use DCF77 time.

Remarks on discriminating and decoding

With the chain of records – one for each modulation period, spoiled or

correct – the first step is to discriminate the values .tim and .per.

We define a stucture for a (uint32_t) value range:

/** Values for discrimination of duration. */

typedef struct {

/** Index.

* The lowest value in a chain (array or enum) shall get the index 0. */

unsigned i;

/** Value.

* This is the upper bound value of the range. <br />

* The highest value in a chain (array or enum) is implied as the maximum

* possible / measurable value. */

uint32_t v;

/** Name.

* This is a short (5 character max.) name of the discrimination range. */

char n[6];

/** Charakter.

* This is a recognisable character for the discrimination range, unique

* for the complete chain. It may be used for (narrow) logs instead of .n */

char c;

} durDiscrPointData_t;

For modulation period (.per) and modulation time (.tim) we define five ranges each two of them good and three bad (below, in beetween and above):

/* Discrimination values for the 15% modulation time. */

durDiscrPointData_t timDiscH[5] = {

{0, 60000, "spike", 's'}, // 0 .. 59.9 ms modulation spike

{1, 128999, "false", 'F'},

{2, 130000, "undef", 'u'},

{3, 228000, "true", 'T'},

{4, MXUI32, "error", 'e'} };

/* Discrimination values for the modulation period. */

durDiscrPointData_t perDiscH[5] = {

{0, 960000, "below", 'b'},

{1, 1040000, "secTk", 'S'}, // seconds tick

{2, 1960000, "undef", 'u'},

{3, 2040000, "minTk", 'M'}, // end minute tick (last two seconds)

{4, MXUI32, "error", 'e'} };

Depending on the receivers, their quality and perhaps filters extra sets with other values are provided. In any case, obviously, the array length is 5. So one optimal discriminating function getting the array and a value returning the entry:

/* Discriminating a value.

* @param table discrimination table of length 5. With other lengths the

* function will fail. Must not be null.

* @param value the number to be discriminated

* @return the lowest table entry with value < table[i].v

*/

durDiscrPointData_t * disc5(durDiscrPointData_t table[], uint32_t const value){

if (value < table[1].v) {

if (value < table[0].v) return & table[0];

return & table[1];

}

if (value < table[3].v) {

if (value < table[2].v) return & table[2];

return & table[3];

}

return & table[4]; // Note: table[4].v (MXUI32 above) is never used

} // disc5(durDiscrPointData_t const *, uint32_t const)

When discrimination both the modulation time (.tim) and the period (.per)

we get four good outcomes:

• F.S false . second tick

• T.S true . second tick

• F.M false . end minute tick (2 seconds)

• T.M false . end minute tick (2 seconds)

All other combinations are bad. Without bad ones we have a chain of true

and false only, we can put indices respectively second numbers 0 .. 58 on

and we can decode.

And ideally each time stamp .tic of a modulation period would mark a “real”

atomic second.

But, alas, we get outages and spikes of all sorts leading to over 100 instead of 59 modulation periods per minute. With good receiver modules and antenna positioning you get very few disturbance. But yet, they occur.

Filtering spikes with pigpiod

On common sort of (AM) disturbances are short – often sub millisecond – spikes either as outage of the full modulation signal or as bursts appearing as full signal instead of 15% amplitude. Both disturbances can get in the range of 40 ms and more.

Spikes could be wiped away with a simple de-bouncing algorithm ignoring all signal changes below a minimal duration. And, fortunately, pigpiod offers this feature for any input captured by call back function.

if (dcfGlitch > 30000) dcfGlitch = 0;

set_glitch_filter(thePi, dcfGpio, dcfGlitch);

With glitch filtering the signal change call back, of course, would come later, but the time stamp is still correct.

The spike or glitch filter value can be in the range of 0 (no filter) to

30000 µs. After many experiments (over weeks) we keep it below 10ms.

dcf77onPi --glitch 9999 >> logs/dcf77test32cAnG.log &

It emerged that higher values might filter out many seconds periods in sequence. Hence, one might detect “no reception at all” respectively “receiver off” wrongly.

An extra filter for modulation disturbances

The extra gain of a 30ms (maximum) glitch/spike filter compared with 10 ms is marginal with good receivers. And anyway, the shortening of a period below e.g. 400ms by a spike could not be handled by pigpiod’s glitch filter. These cases do occur and in most cases they lead to two periods where one should be. Without extra measures all counting and decoding hence on ist lost for the rest of the minute.

A relatively simple extra filter therefore is holding back the first occurrence of ?.b and add this period correctly to next. By this most of those cases could be repaired. The log (Fr, 29.01.2021 14:16) shows a minute otherwise spoiled in second 41:

### .tic .tim sec dis .per system time -cbck decode

DCF77 1.839.060.809 184080 36: T.S 1000492 14:17:35.138 -.185

DCF77 1.840.061.301 84361 37: F.S 998913 14:17:36.238 -. 85

DCF77 1.841.060.214 80060 38: F.S 998333 14:17:37.138 -. 80

DCF77 1.842.058.547 186510 39: T.S 1004452 14:17:38.133 -.187

DCF77 1.843.062.999 79390 40: F.S 1002533 14:17:39.238 -. 80

DCF77 1.844.065.532 28300 41: s#b 53930 14:17:40.135 ignor= // spiky |

DCF77 1.844.119.462 174560 41: T=S 994862 14:17:41.087 -. 29 29.mm. // v

DCF77 1.845.060.394 180051 42: T.S 1004343 14:17:41.232 -.180

DCF77 1.846.064.737 79360 43: F.S 996692 14:17:42.233 -. 79

DCF77 1.847.061.429 181361 44: T.S 1003933 14:17:43.136 -.181 Day:Fr

DCF77 1.848.065.362 175890 45: T.S 994952 14:17:44.235 -.176

DCF77 1.849.060.314 82120 46: F.S 1003043 14:17:45.234 -. 82

DCF77 1.850.063.357 74190 47: F.S 997652 14:17:46.134 -. 75

DCF77 1.851.061.009 82901 48: F.S 1002913 14:17:47.131 -. 83

DCF77 1.852.063.922 78590 49: F.S 997822 14:17:48.136 -. 79 dd.01.

This moderately “intelligent” filter rescues most of those cases (which are quite seldom with good receiver modules). There are some samples where this algorithm failed while adding the spiky period to the one before would have saved that case. Well, implementing that is feasible but according to our data not worth the effort – and the reduced readability of the program.

Final remarks

On a Pi we implemented receiving and decoding DCF77 with inexpensive AM receiver modules. With the reception tick and the “call back tick + call back system time” pair we have all data to correct or set the system time. Hence, we have a (redundant) time source to replace or substitute NTP. It can also synchronise distributed systems in a closed network and or provide a NTP server there.

The full code can be found in the SVN repository weinert-automation.de/svn/.

References

Weinert, Albrecht, “Time synchronisation in local nets”, 2021 post

Weinert, Albrecht, “Raspberry for remote services”, 2018 – 2020 publication

N.N, Joan, “pigpio Daemon” 2020 documentation

PTB “DCF77” 2004 German survey

Comments

Want to leave a comment? Visit this post's issue page on GitHub.For commenting you will need a GitHub account.

This post shares the issue / comments with timeSyncLocNet.html.